The Python GIL

A story

Let’s imagine that you’re trying to optimize some code that computes statistics about how much time users spend on your website. You have a list of objects for each user - where each object itself is a list representing the amount of time a user spent on your website across several sessions. Your psuedocode looks something like this:

def get_time_spent(users):

user_to_time = {}

for (user_id, user_sessions) in users:

total_time_spent = sum(user_sessions)

user_to_time[user_id] = total_time_spent

return user_to_time

This code works, but you’re concerned about the time it takes, since the list of users and user_session is very large. You remember threads and know that this code will run on an 8-core machine, so you decide to split up the users list into 8 chunks and spin up 8 different threads. You quickly conclude that your code will now run about 8x faster, save for any overhead taken up in chunking the list and thread management - you don’t have to worry about things like locking since each thread is working on its own component of the data.

All you have to do is create the threads, and tell each one to run the above get_time_spent function on their distinct list of users:

def threaded_time_spent(users):

user_chunks = chunk_list(users, 8)

threads = [Thread(target=get_time_spent, args=(chunk,)) for chunk in user_chunks]

for t in threads:

t.start()

for t in threads:

t.join()

After coding this up, you run some basic performance tests and realize that your new code actually takes longer to execute than your old code - a far cry from the 8x performance gain you had anticipated.

You’re confused, and begin to look for a bug in your threading implementation, but find nothing. After doing some research, you come across the Global Interpreter Lock, and realize that it effectively serializes your code, even though you wanted to be able to take advantage of multiple cores.

What the hell is that, and why does it even exist in Python?

What does the GIL do?

Simply put, the GIL is a lock around the interpreter. Any thread wishing to execute Python bytecode must hold the GIL in order to do so. This means that at most one thread can be executing Python bytecode at any given moment. This effectively serializes portions of multithreaded programs where each thread is executing Python bytecode. To allow other threads to run, the thread holding the GIL releases it periodically - both voluntarily when it no longer needs it and involuntarily after a certain interval.

Why does Python have a GIL?

First, as an aside, Python doesn’t technically have a GIL - the reference implementation, CPython, has one. Other implementations of Python - such as Jython and IronPython - don’t have a GIL, and have different tradeoffs than CPython due to it. In this post, I’ll mostly be focusing on the GIL as it is implemented in CPython.

The GIL was originally introduced as part of effort to support multithreaded programming in Python. Python uses automatic memory management via garbage collection, implemented with a technique called reference counting. Python internally manages a data structure containing all object references that can be accessed by a program, and when an object has zero references, it can be freed.

However, race conditions in multithreaded programming made it so that the count of these references could be updated incorrectly, making it so that objects could be erroneously freed or never freed at all. One way to solve this problem is with more granular locking, such as around every shared object, but this would create issues such as increased overhead due to a lot of lock acquire/release requests, as well as increase the possibility of deadlock. The Python developers instead chose to solve this problem by placing a lock around the entire interpreter, making each thread acquire this lock when it runs Python bytecode. This avoids a lot of the performance issues around excessive locking, but effectively serializes bytecode execution.

How does the GIL impact performance?

Let’s consider two examples to illustrate the difference in performance for CPU-bound and I/O bound threads. First, we’ll create a dummy CPU bound task that just counts down to zero from an input. We’ll also define two implementations that call this function twice - one that just makes two successive calls, and another that spawns two threads that run this function, and then joins them:

def count(n):

while n > 0:

n-=1

@report_time

def run_threaded():

t1 = threading.Thread(target=count, args=(10000000,))

t2 = threading.Thread(target=count, args=(10000000,))

t1.start()

t2.start()

t1.join()

t2.join()

@report_time

def run_sequential():

count(10000000)

count(10000000)

The report_time decorator is a simple decorator that uses the time module to report how long the function took to execute. Running this script 10 times and averaging the result gave me an average of 1.53 seconds for sequential execution, and 1.57 seconds for threaded execution (see results) - meaning that despite having a 4-core machine, threading here did not help at all, and in fact marginally worsened performance.

Now let’s consider two I/O bound threads instead. The following code runs the select function on empty lists of file descriptors, and times out after 2 seconds:

def run_select():

a, b, c = select.select([], [], [], 2)

@report_time

def run_threaded():

t1 = threading.Thread(target=run_select)

t2 = threading.Thread(target=run_select)

t1.start()

t2.start()

t1.join()

t2.join()

@report_time

def run_sequential():

run_select()

run_select()

_, threaded_time = run_threaded()

_, seq_time = run_sequential()

print(f'{threaded_time} with threading, {seq_time} sequentially')

As expected, the sequential execution takes 4 seconds, and the threaded execution takes 2 seconds. In the threaded model, the I/O can be awaited in parallel. When the first thread runs, it grabs the GIL, loads in the select name and the empty lists along with the constant 2, and then makes an I/O request. Python’s implementation of blocking I/O operations drops the GIL and then reacquires the GIL when the thread runs again after the I/O completes, so another thread is free to execute. In this case, the other thread can run almost instantly, making a call to select as well. This process of yielding the GIL during blocking I/O operations is similar to cooperative multitasking.

On the other hand, CPU-bound threads don’t voluntarily yield the CPU to other threads, and instead have to be forcibly switched out to allow other threads to run. In Python 2, there was a concept of “interpreter ticks”, and the GIL is forcibly dropped every 100 ticks if the thread hasn’t voluntarily given it up. In Python 3, this was switched (and the GIL was in general revamped) to be a time interval, which is by default 5 milliseconds. Both intervals can be reset with sys.setcheckinterval() and sys.setswitchinterval() respectively.

The main takeaway is that the GIL only inhibits performence when you have several CPU-bound threads that you’d like to execute across multiple cores, since the GIL serializes them. Parellizing I/O bound work via multiple threads is still a good bet.

Working around Python’s GIL

There are still a few things that we can do to potentially optimize performance of CPU-bound Python code across multiple threads, despite the GIL. The first thing to consider is using the Process module. Process has an API similar to that of thread, but it spawns an entirely separate process to run your function. The good news is that the new process has its own interpreter, so you can take advantage of multiple cores on your machine. Porting the above threaded code to use Process shows the expected ~2x performance gain. However, processes are much heavier than threads, which brings in efficiency concerns if you’re creating a nontrivial number of separate processes. In addition, there’s more overhead involved in using IPC mechanisms rather than simply communicating with shared variables with threads.

As a more involved task, it may be worth considering porting your CPU-bound code to C, and then writing a C extension to bridge your Python code to the C code. This can provide significant performance advantages, and several scientific computing libraries such as numpy and hashlib release the GIL in their C extensions.

By default, code that runs as part of a call to a C extension is still subject to the GIL being held, but it can be manually released. This is common for blocking I/O operations as well as processor intensive computations. Python makes this easy to do with two macros: Py_BEGIN_ALLOW_THREADS and Py_END_ALLOW_THREADS, which save the thread state and drop the GIL, and restore the thread state and reacquire the GIL, respectively.

Details around the GIL implementation

The GIL is implemented in ceval_gil.h and used by the interpreter in ceval.c. A thread waiting for the GIL will do a timed wait on the GIL, with a preset interval that can be modified with sys.setswitchinterval. If the GIL hasn’t been released at all during that interval, then a drop request will be sent to the current running thread (which has the GIL). This is done via COND_TIMED_WAIT in the source code, which sets a timed_out variable that indicates if the wait has timed out.

The running thread will finish the instruction that it’s on, drop the GIL, and signal on a condition variable that the GIL is available. This is encapsulated by the drop_gil function.

Importantly, it will also wait for a signal that another thread was able to get the GIL and run. This is done by checking if the last holder of the GIL was the thread itself, and if so, resetting the GIL drop request and waiting on a condition variable that signals that the GIL has been switched.

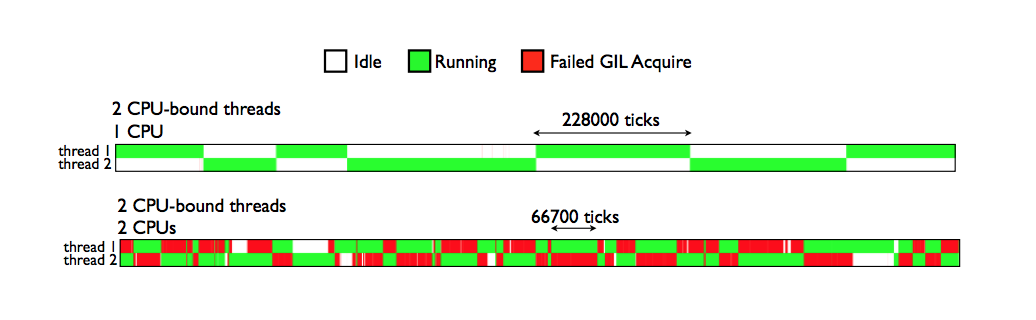

This wasn’t the case in Python 2, where a thread that just dropped the GIL could potentially compete for it again. This would often result in starvation of certain threads, due to how the OS would schedule these threads. For example, if you had two cores, then the thread dropping the GIL (let’s call this t1) could still be running on one core, and the thread attempting to acquire the GIL (let’s call this t2) could be scheduled on the 2nd core. What could happen is that since t1 is still running, it could re-acquire the GIL before t2 even gets a chance to wake up and see that it can acquire the GIL, so t2 will continue to block since it wasn’t able to acquire the GIL, and then wake up and try again repeatedly. This would result in something dubbed the GIL battle:

The GIL battle (source)

The GIL battle (source)

This would frequently happen for CPU-bound threads left running on a core in Python 2. This could result in I/O bound threads being starved and lots of extra signalling on condition variables, reducing performance. These slides have some more details about the Python 2 GIL.

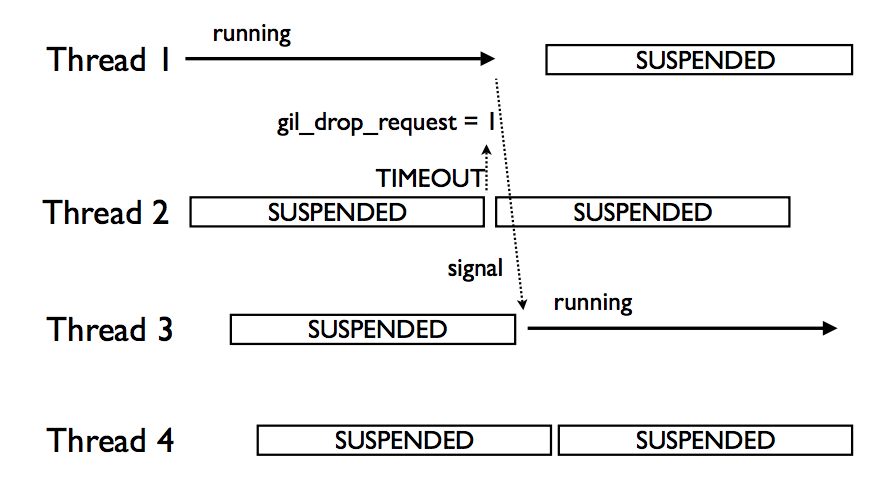

There’s one important subtelty in the case of multiple threads. Since Python doesn’t have its own thread scheduling and wraps POSIX/Windows threads, scheduling of threads is left up to the OS. Therefore, when multiple threads are competing to run, the thread that issued the GIL drop_request may not actually be the thread that acquires the GIL (since a context switch could occur, another waiting thread could see that the GIL is available, and acquire it). These slides have some more details about this.

GIL behavior with multiple threads (source)

GIL behavior with multiple threads (source)

What could (but doesn’t) happen is that the thread that was unable to acquire the GIL, but still timed out on waiting for it, could continue to issue the drop_request and attempt to re-acquire the GIL. This would essentially be like a spin lock - the thread would keep polling for the GIL and demanding for it to be released, using up CPU to accomplish nothing.

Instead, on a time out, a check is also done to see if the GIL has switched in that time interval (i.e. to another thread). If so, then this thread simply goes to sleep waiting for the GIL again. While this does in a sense reduce “fairness” (in the sense that the thread that requested the GIL should get it next), it also dramatically reduces GIL contention, compared to Python 2, and is somewhat of a necessary tradeoff since Python doesn’t control when its threads run.

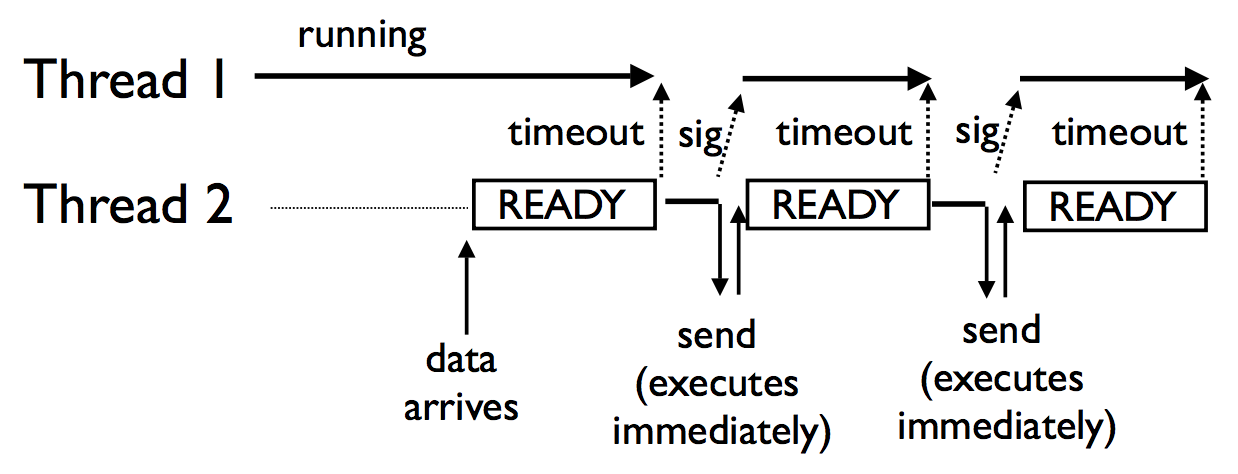

One criticism about the new GIL relates to the above point of the “most deserving” thread (i.e. the thread that sent the drop_request) getting the GIL. This is largely because thread scheduling is entirely up to the OS, but also has some repercussions for I/O operations that complete very quickly. Since any I/O operation will release the GIL, CPU-bound threads will restart and use their entire time slice before yielding back, and the I/O bound thread has to go through the entire timeout process to re-acquire the GIL. This can create somewhat of a convoy effect of quick-running I/O operations having to queue up to acquire the GIL:

Convoy effect with the new GIL (source)

Convoy effect with the new GIL (source)

Summary

The GIL is an interesting part of Python, and it’s cool to see the different tradeoffs and optimizations that were done in both Python 2 and Python 3 to improve performance as it relates to the GIL. The seemingly small changes to Python 3’s GIL (such as the time-based, as opposed to tick interval and reduction of GIL contention) emphasizes just how important and nuanced issues such as lock contention and thread switching are, and how hard they are to get right.